Chapter 10–Atmospheric Effects

Sky Blue

The sky gets lighter near the sun–solar glare.

The sky shifts in value from zenith to horizon. It gets darker as you go up.

The sky color changes in value, hue, and chroma.

Sky color is lighter and warmer near the sun–more white light is scattered there.

When mixing sky colors, shift your mixtures from top to bottom and from side to side.

Atmospheric Perspective

Darkest areas are affected first, becoming lighter and bluer.

Illuminated sides of objects lose color saturation, becoming grayer as they go back.

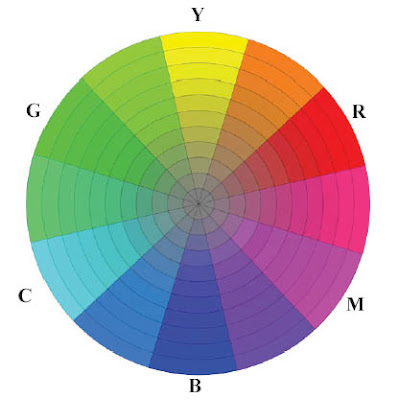

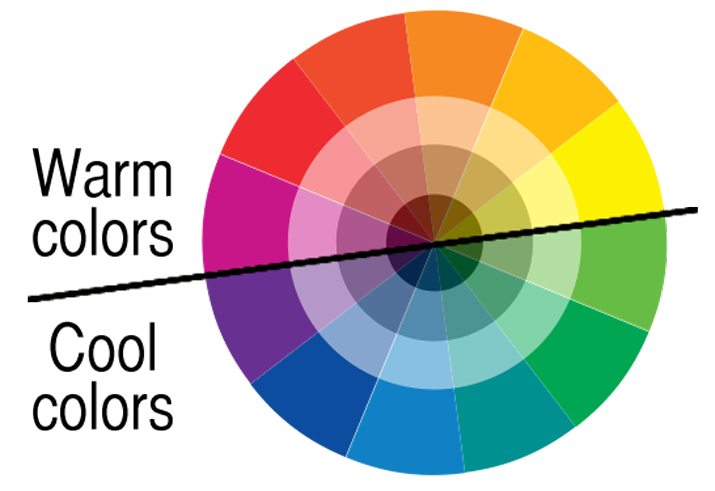

Warm colors grow duller and cooler.

Contrast between light/shadow sides of objects reduce until everything is flattened into silhouette.

Things look blurrier.

White objects grow warmer as they go further away, like the sun and clouds and such. White objects are visible for the longest amount of time at a distance.

Atmospheric perspective only happens if the thing is illuminated.

It’s more intense when there’s dust, moisture, haze, or smog.

Reverse Atmospheric Perspective

When there’s vapor or dust or clouds by the sun, atmospheric perspective is reversed and things get warmer as they go back.

Relatively rare, brings a feeling of strangeness or excitement.

Golden Hour Lighting

Dawn and Dusk–colors become bold and dramatic.Sunlight travels through more miles of atmosphere at this angle. The sky is a richer blue. The remaining sunlight is weaker in brightness and more orange and red in color. Forms lit by this light are golden and shadows are very blue.

Sunsets

Don’t show up well in photos, but good to paint from observation.

Many colors–sun interacts with dust, air, and clouds. More moisture and dust–more reds and yellows. Brightest red-orange from where the sun crosses the horizon.

Weaker light glow at antisolar point–opposite of the sun.

Warm colors drain out, leaving violet.

Reverse colors in the morning.

Fog, Mist, Smoke, Dust

Contrast drops off rapidly as forms recede. The sun can’t penetrate far, so light reaching the ground seems to come from everywhere.

Rainbows

Have cool symbolic meaning.

Rainbows don’t exist in a particular geographic space, but as an angle in relation to the viewer.

Antisolar point is the center of the rainbow. All shadows in the scene should orient toward that point.

Secondary rainbow–reversed color sequence, weaker. Between rainbows is a darker band–looks darker because of additional light reflected.

Colors of rainbow should always be lighter than background.

Skyholes and Foliage

Silhouette of tree is almost never solid. Smaller skyholes should be painted a little darker than the sky–often contain a network of fine branches and tiny leaves. Make the skyholes various sizes and give them a ragged character.

Foliage has different degrees of transparency.Spring leaves only partially block sky. Get darker in the summer. Different kinds of trees are more ore less opaque and have different numbers of skyholes.

Sunbeams and Shadowbeams

Sunbeams occur in these conditions:

–high screen of clouds, foliage, or architecture is punctuated by a few openings. Perforated layer needs to block most of the light to allow a darker backdrop against which the sunbeams can be seen.

–air is filled with dust, vapor, smoke, or smog

–view is toward the sun–beams are nearly invisible when you’re looking away from light source.

Could see these things in a variety of places.

Edges of beam get more fuzzy as they go away from light source.

Sunbeam influences shadow values of the forms even more than they affect light-side values.

Shadowbeams are rare. Occur when a jet contrail aligns with the line of sight.

Dappled Light

Spaces in a tree create little pinhole projectors. Projections of circular shape of the sun.

Higher tree canopy makes bigger circles with softer edges.

Cloud Shadows

Use cloud shadows to control a viewer’s attention.

Dutch landscape painters frequently used this method–adds interest to a flat landscape.

Illuminated objects attract attention when there’s a lot of shadow, and vice versa.

Three rules:

–margin between light and dark needs to be a soft edge (about half a city block in size).

–size and spacing of cloud shadows needs to match the clouds visible in the sky.

–shadow area is darker and cooler than the sunlit area. Shadow doesn’t have as much of a blue cast as the cast shadows on a clear day.

Illuminated Foreground

Kind of unusual setup, where the foreground is bright and the middle distance is in shadow. (Usually, the foreground is shadowed.) Can concentrate attention on the foreground.

Snow and Ice

Snow is denser and whiter than clouds or foam. It picks up the colors of whatever is around it, especially in shadow. Shadows–color of the sky.

Has a lot of subsurface scattering, especially when it’s newly fallen.

Older snow is darker and shinier. Water appears darker next to snow since snow is so white.

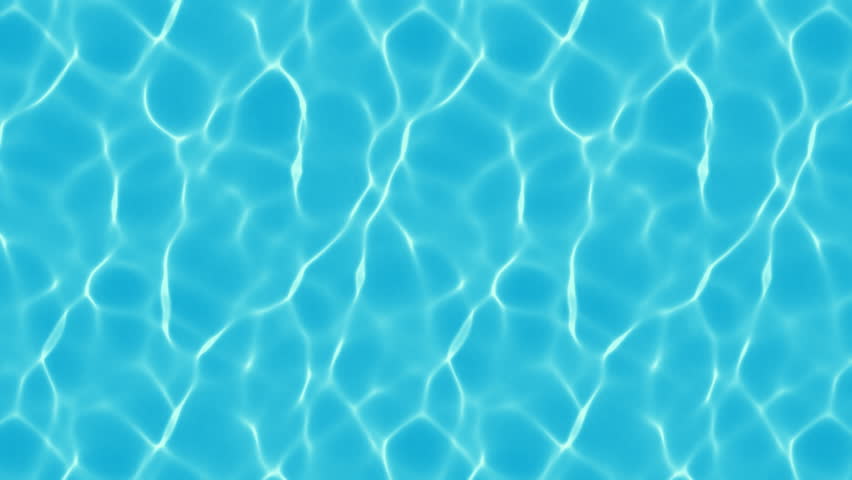

Water: Reflection and Transparency

Reflection and Refraction

Water is only as reflective as a mirror when you look straight across it at a shallow angle. Steeper angle—more light entering water.

When you look straight down–water looks darker, not much light reflects from the sky.

Water is more transparent when it’s nearer to you.

Reflection of dark objects is affected by the amount of sediment in the water and the amount of light shining in the water.

Dirty water that’s illuminated makes the darks turn lighter and browner. When there’s no direct light touching the water, muddy water reflects as well as clean water.

Vertical lines are preserved in reflections, while the horizontal lines are broken by the water’s uneven surface.

You can’t cast a shadow over deep, clean water.

If you do get a shadow–in silty water–it will have diffuse edges.

Mountain Streams

Stones in water shift to darker, warmer versions of the local color of the rock.

Deeper than 3 feet, colors get bluer and the bottom surface gets less distinct.

Details on the bottom are distorted by the ripping surface. Paint loosely.

Shallows–warmer colors. Colors shift to blue/green in deeper pools.

Color Underwater

Water filters out colors of light.

Red is gone by 10 feet

Orange and yellow are gone by 25 feet.

Blues and violets are all that remain. Only violet and ultraviolet light exist at the deepest depths.

Here’s a picture that shows the same scene with and without color correction (as if the colors could show underwater further).

Chapter 11: Light’s Changing Shadow

Serial Painting

Serial painting is making multiple plein-air studies of the same subject under different conditions

Try storyboarding your day! Make little studies of landscapes as you pass on a train or scenes from your life. Watch how the light changes.

When serial painting, keep the drawing consistent so the only variable is the light.

Don’t look at previous studies as you paint. Try painting at different times of day and different seasons of the year

Try to find a spot to paint that has different eleents in it, like mountains, a house or other planes facing different directions, etc. Give yourself stuff to work with!

Here’s color scripting for the movie “Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs.”

Here’s color scripting for the movie “Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs.”